Entering the experience machine

If we can make our own realities, what should we build?

You might have seen the trend. People are running ordinary photos through ChatGPT to make them look like scenes from a Studio Ghibli film — soft, enchanted, slightly otherworldly. I tried it on a few snapshots from my own life: a photo with friends, a city street I walk every day. The results were undeniably charming. But that wasn’t what caught my attention.

This wasn’t pixelated dogs or uncanny hands. These were cohesive, stylized, emotionally resonant images, created in seconds from mundane inputs. It’s a quiet leap forward in creativity-on-demand — and a reminder that the bar for what machines can do is rising fast. And that’s the point: the Ghibli trend isn’t just an aesthetic fad. It’s a playful demo of a deeper shift. The same model that can turn a tourist snapshot into a fantasy still is also getting better at coding, reasoning, persuasion, and planning. We’re watching frontier models progress — not just in benchmarks, but in everyday life.

Zoom out, and the Ghibli filter is a trivial use case. But it gestures at something bigger: a world where powerful systems increasingly shape what we see, what we choose, and what we believe. That opens up extraordinary possibilities, but also forces us to ask questions not just about the tools we use, but also about the goals we set. What does real progress look like when reality itself can be remade to match our desires? And how should we think about tradeoffs — between aesthetic delight and accuracy, short-term gratification and long-term stability, what feels good and what’s actually true?

What I’ve written

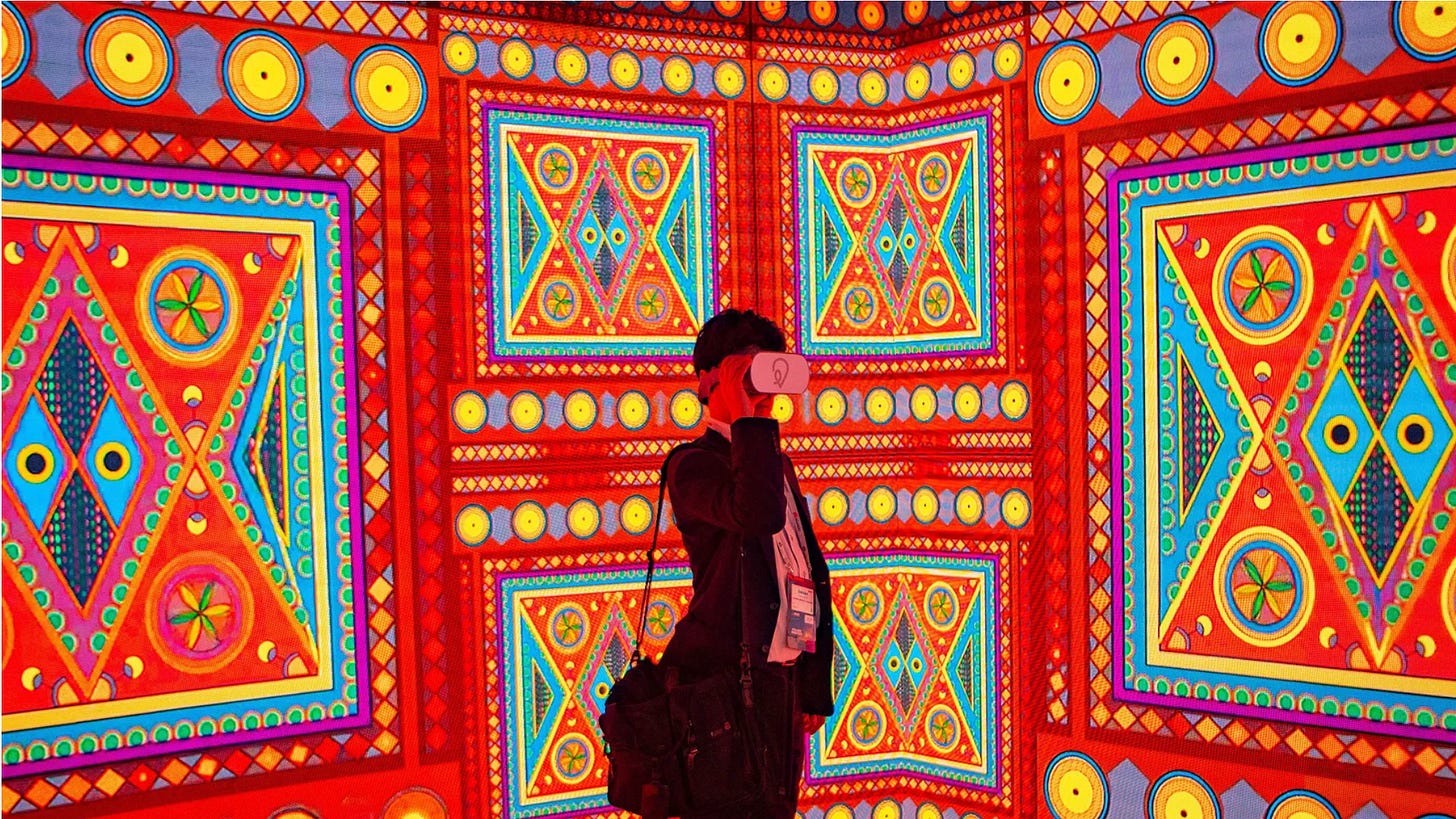

In March 2024, The Matrix had its 25th anniversary — and Robert Nozick’s “experience machine” turned 50. I wrote for BBC Future about this thought experiment, which feels more relevant now than ever. Nozick asked whether we’d choose to live in a simulated world that perfectly fulfills our desires, even if we knew it wasn’t real. He argued that most people wouldn’t — that we crave something deeper than pleasure, and value reality for its own sake.

Fifty years later, we’re inching closer to that dilemma. People are falling in love with chatbots, spending years in immersive games, and curating digital lives that may feel more compelling than the real thing. That doesn’t mean reality is losing — but it does mean we need clearer internal compasses. In the piece, I explore how Nozick’s thought experiment holds up today, and why our concept of “reality” may be shifting as technology gets better at giving us exactly what we want.

Unlike either The Matrix or Nozick’s machine, this won’t be a single decision: AI will be increasingly intertwined with our lives in many ways. Every day, we’ll make choices about how and when to use it. That choice, over time, accumulates into a weighty one. Reading the full article when the AI summary is shorter, or spending time with friends over Claude prompted-into-therapist are examples of decisions that feel dull or effortful now, but might nourish something deeper over time. But this also gives us a chance to shape norms and defaults before they calcify — to build in friction, reflection, or values-aligned nudges while the paths are still forming.

Similar to the Matrix, Nozick's experience machine would be able to provide the person plugged into it with any experiences they wanted – like "writing a great novel, or making a friend, or reading an interesting book". No one who entered the machine would remember doing so, or would realise at any point that they were within it. But in Nozick's version, there were no malevolent AIs; it would be "provided by friendly and trustworthy beings from another galaxy". If you knew all that, he asked, would you enter the experience machine for the rest of your life?

Keep reading: 'Experience machines': The 1970s thought experiment that speaks to our times

In day to day life, we make similar judgments about what feels real and counts as meaningful. In a piece for Nautilus Magazine, I explored why we tend to devalue art made by AI, even when it’s visually identical to human work.

A series of experiments found that people consistently rated AI-labeled images as less valuable, less skillful, and less creative than the same images labeled human-made. This was true even when they reported that they could not distinguish between them. One reason may be what philosopher Robert Nozick called the “authenticity intuition” — the idea that we care about reality, not just appearances.

But the results also point to a deeper tension: even as AI systems become better at mimicking human output, we’re not always willing to treat those outputs as equivalent. That gap — between capability and perception — could shape how AI is adopted, trusted, or resisted in domains that depend on meaning, not just performance.

The authors of the study first became interested in how we value AI-driven art when a fellow Columbia researcher began holding exhibitions of machine-made works in 2016. “People would receive it differently if he gave more credit to the machine for the work,” says first author Blaine Horton, a former performing artist and current doctoral student at Columbia Business School. “They’d say it was cool, but not terribly interesting or creative. But when he took more of the credit for the work, it appeared people responded more positively.”

Keep reading: We’re biased against AI-made art

What I’ve been reading

A look the rise of ‘buy now, pay later’ services, and how they are helping people get what they want today — at the risk of entrenching debt, weakening consumer protection, and undermining long-term financial stability.

What companies like Klarna once characterized as paradigm-busting behavior—young people rejecting stodgy banks in favor of more freeing forms of finance—now looks like the crest of yet another credit cycle, a familiar note in the motif of American consumption.

An investigation into a dramatic downsizing of America’s public health infrastructure under the banner of efficiency, which asks whether we’re mistaking bureaucratic function for bureaucratic bloat.

It does not take a genius to understand that pushing out 20,000 workers at our preeminent health agencies won’t make Americans healthier. It’ll just mean fewer health services for our communities, more opportunities for disease to spread, and longer waits for lifesaving treatments and cures.

An argument that real advancement means not just chasing what’s new, but taking responsibility for the problems progress creates — from toxic drugs to smog-filled cities to deadly electrical fires.

Inventing the automobile is progress, and solving the smog it creates is further progress... This isn’t a failure of progress; it is the nature of progress.

What I’ve been thinking about

The weather warmed up this week in New York, and suddenly the city flipped a switch — café tables spilling onto sidewalks, crowds laying out in Central Park, everyone shedding their coats at once. It’s the season of surface-level joy: everything brighter, lighter, easier.

But I’ve been thinking about how easy it is for everything to become surface-level. Credit apps that make you feel richer than you are. Policies that look lean and efficient until they quietly gut what matters. Advances that dazzle — and distract. And yet, that dazzle is also real. Joy and enchantment aren’t inherently shallow; they just need anchoring.

This month’s pieces are all, in their own way, about that tension: the pull of what feels good versus the value of what’s real. About how progress sometimes means going deeper, not faster — and noticing when delight comes with a cost. But also about how we might keep the delight, without losing the depth.