Iodine deficiency is making a comeback

The fragility of progress in public health

Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about the stories we tell ourselves about progress—and how quickly those stories can unravel. Writing and reading about topics from the reemergence of iodine deficiency in the U.S. to the global rise of measles and even scurvy have brought this into sharp focus. These are health problems we know how to solve, yet they persist.

At the same time, trust in science has seriously declined. The creation of the Department of Government Efficiency — a planned United States presidential advisory commission to be led by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy aiming to reduce federal spending — and related quips about cutting research funding are a prominent symptom.

It’s a reminder that progress in public health depends on more than solutions; it hinges on the systems that sustain them. Trust in science, adequate funding, and collective responsibility are as vital as the interventions themselves. The headlines this month highlight how fragile progress can be—and why it’s worth fighting to hold onto.

What I’ve written

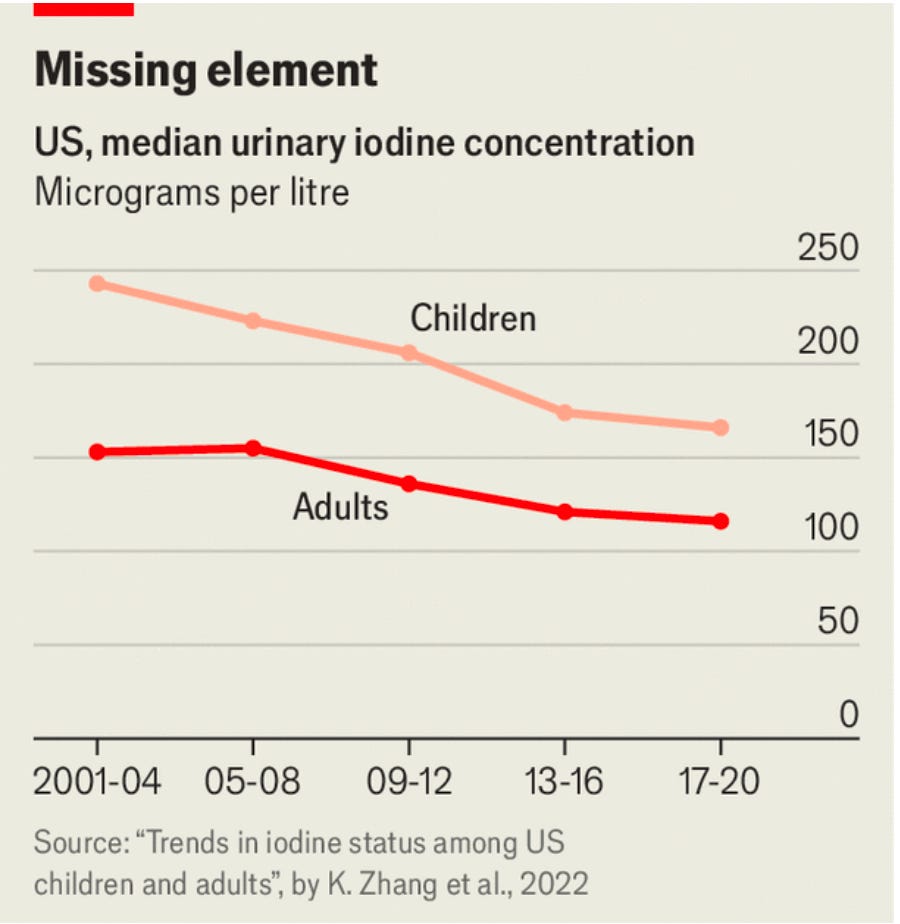

This month, in The Economist, I explored a health issue that has quietly re-emerged in the United States: iodine deficiency. A century ago, in 1924, the U.S. rolled out iodized salt and functionally eliminated the problem. That public health victory was, it seems, temporary. Recent studies show that iodine levels have dropped by over half between the 1970s and 1990s and further still since then. Insufficiency affects a significant portion of American women, particularly those of reproductive age.

It’s fascinating—and troubling—to see how something as simple and effective as iodized salt has quietly fallen off the radar. Despite being preventable, iodine deficiency impacts 2 billion people globally and remains the leading cause of preventable intellectual disability.

Salt iodisation was never federally mandated. This has had several knock-on effects. For one, only about half of American table salt (which makes up 11% of the salt Americans consume today) is actually iodised. Faddish alternatives, like sea salt or pink Himalayan, tend not to be. More important, the salt used in processed foods—which accounts for a dominant and ever-increasing share of American salt consumption—is also iodine-free.

Changing salt consumption is not the only dietary trend at play. Decreasing demand for meat and fish, both good natural sources of iodine, is also having an effect. According to a study published in JDS Communications in February, one cup of cow’s milk, which is often supplemented with iodine, provides about half the daily intake needed for adult women. Increasingly popular alternatives to dairy, such as oat milk and soy milk, by contrast, typically offer no such benefits.

Keep reading: As wellness trends take off, iodine deficiency makes a quiet comeback

This article has an accompanying audio version here.

I went on The Economist’s daily podcast, The Intelligence, to discuss this article here.

What I’ve been reading

This piece about the rise of science skepticism in the U.S. - and how it is impacting public health policy today.

Public-health officials wonder if they have sufficient clout for the next national emergency. “Science is losing its place as a source of truth,” said Dr. Paul Offit, an infectious-disease physician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “It’s becoming just another voice in the room.”

In October 2023, 27% of Americans who responded to a Pew Research Center poll said they had little to no trust in scientists to act in the public’s best interests, up from 13% in January 2019.

This article about the large jump in measles cases in 2023 due to inadequate vaccine coverage in LMICs.

Measles cases rose 20% last year, driven by a lack of vaccine coverage in the world's poorest countries and those riddled with conflict, the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said on Thursday.

Nearly half of all the large and disruptive outbreaks occurred in the African region where the number of deaths increased by 37%, they said.

"At this moment, every single country in the world has access to measles vaccine, so there's no reason why any child should be infected with the disease and no child should die from measles," WHO's Natasha Crowcroft, a senior technical adviser on Measles and Rubella, told reporters.

This article about the resurgence of Victorian-era diseases in the UK due to declining vaccination rates, poor diets and cuts to public health budgets.

This weekend the British Association of Dermatologists issued an alert about an “unusually high” rate of scabies — a parasitic skin infection typically associated with Victorian workhouses. Just days earlier, doctors had warned in the BMJ of a resurgence in people developing scurvy due to not eating enough fruit and vegetables. Meanwhile, cases of the sexually transmitted disease syphilis, which was rife in the 18th and 19th centuries, are the highest they’ve been since 1948.

What I’ve been thinking about

Recently, I’ve been struck by how fragile progress can feel, especially in the context of public health. As I’ve read about the resurgence of diseases like measles and even scurvy—yes, scurvy!—it’s hard not to wonder what it says about the systems we’ve built and what happens when they’re left to erode.

This feels particularly relevant now, as conversations about trust in science seem louder and more contentious than ever. Recent data highlights the steady decline in public trust in scientists, with only 73% of Americans expressing confidence in 2023, down from 84% just a few years ago. Among some political groups, the erosion is even sharper, turning this into a cultural and political issue as much as a scientific one.

It’s hard to ignore the parallels: in the U.S., skepticism toward scientific expertise is shaping everything from vaccine uptake to health policy, while in the UK, cuts to public health budgets are allowing conditions that once defined the Victorian era to creep back into modern life.

These stories feel especially poignant as we enter a season where community health is top of mind. The holidays bring families together, but they also remind us of the shared responsibility we have to protect each other.

It makes me think about how we balance individual freedoms with collective good, how we build systems that prioritize prevention over crisis, and how we sustain trust in expertise when it feels like that trust is fraying. Maybe it’s not just about fixing what’s broken, but also about holding on tightly to the progress we’ve already made.