How anemia may be beneficial

The second-order consequences of health interventions

Lately, I’ve been reflecting on how complicated the second-order consequences of interventions can be — and how this dynamic makes improving health and economic outcomes as difficult as it is important. Some programs can be described straightforwardly: a policy to incentivize healthy eating, a financial stimulus to stabilize markets, or an aid program to improve public health. But, as they unfold, they may produce unforeseen effects that ripple across systems, sometimes even counteracting the very benefits they aim to deliver.

When we recognize these complexities, it becomes clear that there’s rarely a one-size-fits-all solution in health or development. Effective interventions require a willingness to adapt, to look beyond the immediate outcomes, and to weigh the broader impacts that may emerge over time. This month, I’ve been reflecting on the importance of this approach—of seeing interventions not as isolated acts, but as pieces of a much larger and often unpredictable system.

What I’ve written

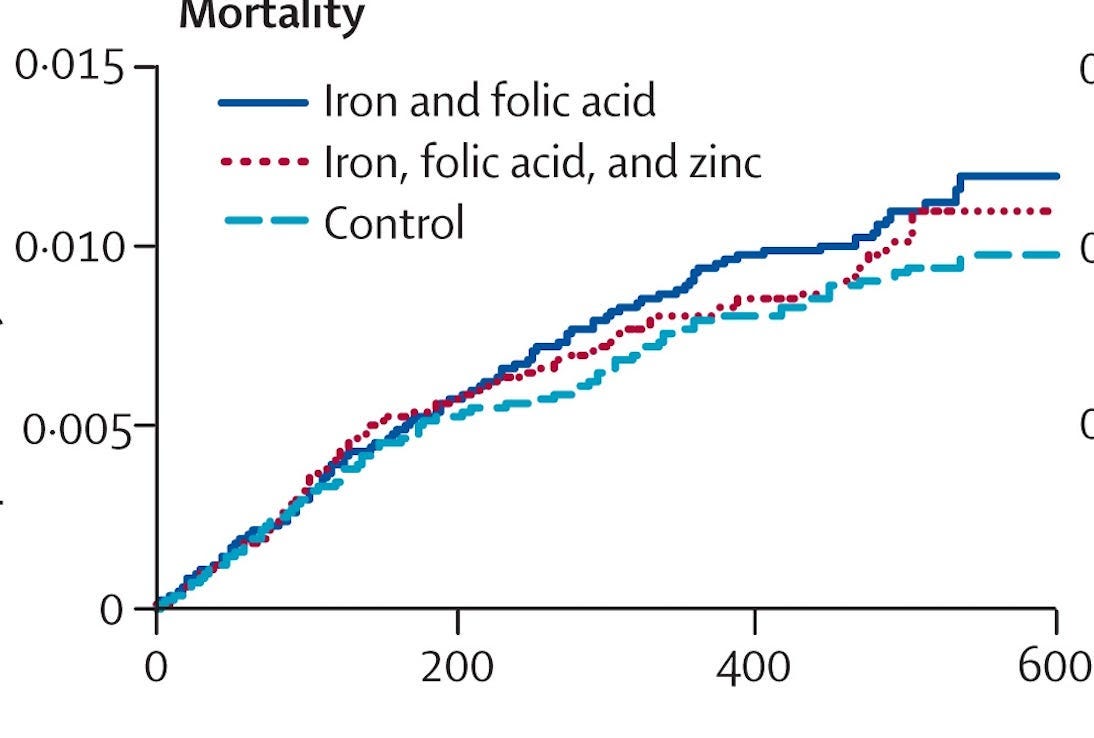

This month, I explored the unforeseen consequences of a nutritional supplementation program in Works in Progress. In 2003, an iron and folic acid supplement randomized control trial in Zanzibar was shut down abruptly when researchers found the treatment increased mortality. Children who received an iron dose were 12% more likely to die from severe illness relative to the control.

Researchers theorize that, in some settings, iron supplementation may inadvertently increase vulnerability to malaria by providing the parasite with a nutrient it needs to thrive. This can result in the intervention having a net-negative impact on recipients’ health and wellbeing, in spite of its benefits in reducing anemia.

The group of parasites that cause malaria are dependent on iron to proliferate. As a result, some evidence suggests that being iron deficient or anemic offers protection against malaria infection. In a 2012 study, researchers followed a cohort of 785 Tanzanian children over three years and found that those who became naturally iron deficient were 60 percent less likely to die than those who did not.

Keep reading: Anemia and Malaria

What I’ve been reading

This paper linking declines in bat populations to a 7.9% increase in infant mortality in impacted countries (through the mechanism of increased insecticide use by farmers).

I use the sudden emergence of a deadly wildlife disease in insect-eating bats—known as white-nose syndrome—to quantify the benefits from their provision of biological pest control. I validate previous theoretical predictions that farmers respond by substituting bats with insecticides; however, because those are toxic compounds, by design, this substitution leads to higher human infant mortality rates in the areas affected by the bat die-offs.

This paper about how economic development, and related urbanization, may increase the risk of zoonotic diseases, or infections that spread between animals and humans.

Three interrelated world trends may be exacerbating emerging zoonotic risks: income growth, urbanization, and globalization. Income growth is associated with rising animal protein consumption in developing countries, which increases the conversion of wild lands to livestock production, and hence the probability of zoonotic emergence. Urbanization implies the greater concentration and connectedness of people, which increases the speed at which new infections are spread. Globalization—the closer integration of the world economy—has facilitated pathogen spread among countries through the growth of trade and travel.

This paper about the economic — rather than educational — returns to universal pre-kindergarten, suggesting that the program may not be particularly helpful for learning outcomes, but that its benefits to parents’ earnings may mean it pays for itself.

Using a randomized lottery design, we estimate the effects of enrolling in a full-day UPK program in New Haven, Connecticut on parents' labor market outcomes as well as educational expenditures and children's academic performance… Enrollment has limited impacts on children's academic outcomes between kindergarten and 8th grade… In contrast, parents work more hours, and their earnings increase by 21.7%. Parents' earnings gains persist for at least six years after the end of pre-kindergarten. Excluding impacts on children, each dollar of net government expenditure yields $5.51 in after-tax benefits for families, almost entirely from parents' earnings gains.

What I’ve been thinking about

Like many in the United States—and elsewhere—the ongoing presidential race has been on my mind. Specifically, I’ve been intrigued by how prediction markets are shaping discourse around the upcoming election. While polls show the U.S. presidential contest as neck and neck, as of when I’m writing this, bets on Kalshi give Trump a 62 percent chance of winning, versus 38 percent for Harris. Polymarket has the race at 65 to 35, and PredictIt shows them at 61 to 43.

This shift has led to a debate about how much to trust market moves as reflecting sentiment. Critics argue that prediction markets may not always reflect true beliefs, suggesting they’re being influenced by “whales” or motivated investors. Meanwhile, others challenge skeptics to put their money where their mouth is if they disagree — pointing out the inconsistency of claiming odds in a prediction market are inaccurate without buying the other side.

What interests me most is how these markets might both reflect and shape voter perceptions. As people see odds fluctuate, it can create a feedback loop where predictions influence expectations, and those expectations then feed back into market behavior. These dynamics in prediction markets reveal just how intricate our systems for interpreting events can be. Whether in health, development, or politics, there’s rarely a simple answer—and that’s exactly what makes these shifts worth watching.

the actual negative results from global health and development are so cool! i remember reading about estimating the impact of programs in a statistical sense, and having some programs not increase welfare at all, but decrease it. glad to know what that looks like in practice!