A lake poised to erupt

And the balance between safety and efficient resource extraction

Welcome back!

Last month’s post explored the shifting landscape of happiness across generations and the health and productivity costs of extreme heat. This time, we're diving into new territory; many of the things I’ve been reading and writing about relate to how physical landscapes shape human development and well-being.

The "What I've written" section takes us to Lake Kivu, at the border between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. It's a place where geology, energy policy, and human safety collide in ways that challenge our usual thinking about development. This theme – environments shaping health and development – also resonates through much of what I’ve read this month, including new research on air pollution in Victorian and early 20th century London and an ambitious housing plan in the Bronx.

Reach out if something in this posts sparks thoughts - I'm always curious to hear what catches your attention or gets you thinking.

What I’ve written

Straddling Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, Lake Kivu’s unique geological composition traps large amounts of carbon dioxide and methane at the lake bottom, posing a potential catastrophic threat to millions living nearby should the lake overturn and the gasses explode outward. Earlier this year, I explored the Rwandan government’s efforts to defuse this risk by extracting methane from the lake - and the ongoing battle over the right balance between safety and resource utilization in the process. With climate week approaching, complex decisions about energy and resource extraction feel especially top of mind.

Lake Kivu is a geological anomaly, a multi-layered lake whose depths are saturated with trapped carbon dioxide and methane. Only two other such lakes—Lake Nyos and Lake Monoun—share these characteristics, and both have erupted in the past 50 years, spewing a lethal cloud of gas that suffocated any humans and animals in its path. When Lake Nyos erupted in 1986, it asphyxiated nearly 2,000 people and wiped out four villages in Cameroon. Folklore in the area speaks of “the bad lake” and its evil spirits that emerged to kill in an instant. Concerningly, Lake Kivu is 50 times as long as Lake Nyos and more than twice as deep. Millions live on its shoreline.

…

However, some experts believe that current efforts to remove gas from the lake may trigger an eruption—and a local extinction event.

“It’s a compromise of safety versus commercial exploitation in the long term,” says Katsev. “If you return the water deep in the lake, you dilute your resource zone for future years. However, if you dump it higher up,” as KivuWatt is currently doing, “the water generates a plume as it sinks downward through the density layer, causing the water to mix vertically. The risk of limnic eruption is linked to this vertical movement.”

Keep reading: This African lake may literally explode—and millions are at risk

What I’ve been reading

This article hypothesizing about the potential health-related causes of economic stagnation in the US beginning in the 1970s:

Americans born after 1947 and before the mid-1960s — the first of whom

were just entering their prime working years in 1971 — did not see economic

gains comparable to those of their predecessors… They had more problems as young children, and they did worse in school in the 1960s, accounting for the educational declines of that era, such as lower test scores and higher dropout rates. Birthweights also declined in the 1980s, a sign that the post-1947 cohort was

less healthy, most of all when it comes to maternal health.

This article about the ICN’s call for a moratorium on recruitment of nurses from 55 countries with pressing health workforce shortages:

The International Council of Nurses (ICN) has called on the World Health Organization (WHO) to consider a “time-limited moratorium of active recruitment of nurses” from countries on the WHO Health Workforce Support and Safeguard List. This follows a “dramatic surge” in the recruitment of nurses from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) by wealthy countries, according to the ICN…

Tonga and Fiji reported losing 20% to 30% of their nurses, primarily to Australia and New Zealand, at the 2024 World Health Assembly (WHA)… The Filipino Department of Health has recently allocated funds to provide nurses with health insurance, housing, and other benefits in an attempt to stem the tide of nurse migration.

This paper analyzing the health impacts of exposure to air pollution in London between 1866 and 1965:

This study provides new evidence on the impact of air pollution in London over the century from 1866-1965. To identify weeks with elevated pollution levels I use new data tracking the timing of London's famous fog events, which trapped emissions in the city. These events are compared to detailed new weekly mortality data. My results show that acute pollution exposure due to fog events accounted for at least one out of every 200 deaths in London during this century. I provide evidence that the presence of infectious diseases of the respiratory system, such as measles and tuberculosis, increased the mortality effects of pollution. As a result, success in reducing the infectious diseases burden in London in the 20th century reduced the impact of pollution exposure and shifted the distribution of pollution effects across age groups

What I’ve been thinking about

The Olympics. There's something fascinating about how they manage to capture global attention every couple of years. For a few weeks, I find myself suddenly caring deeply about sports I've barely heard of, and feeling an unexpected surge of national pride.

The Olympics are an interesting mix of athletic competition, geopolitical theater, and cultural showcase. They bring out the best in human achievement, but also create a more physical playing field to battle out underlying disagreements and tensions.

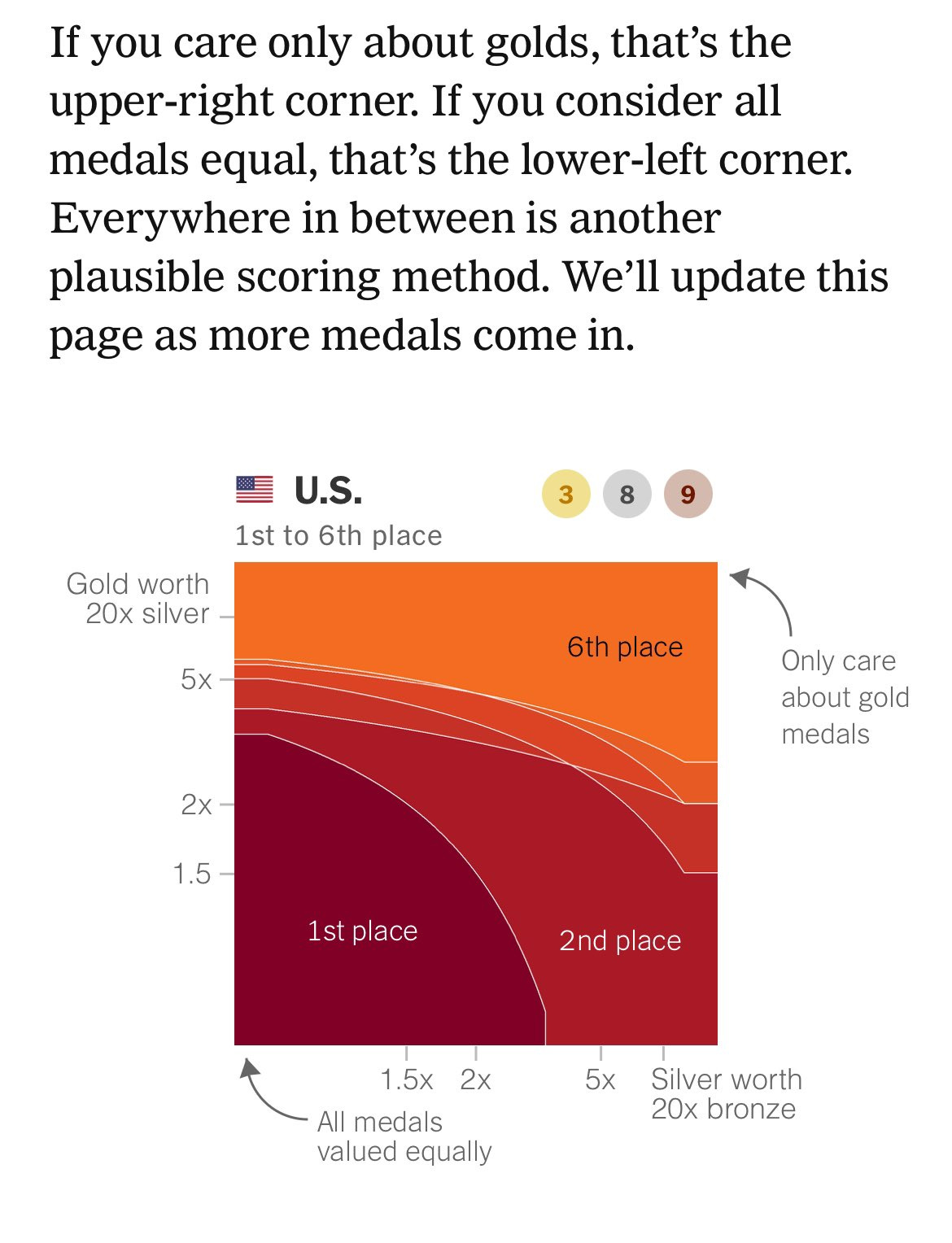

This year, I especially enjoyed the New York Times’ medal count tracker - a more illustrative mid-games snapshot of which is below. The chart offers country rankings based on different relative weight for gold, silver, and bronze medals - showing even a question as simple as ‘who is winning?’ can be subjective.

Whatever your take, there's no denying the Olympics' power to make us collectively hold our breath for the perfect dive, the record-breaking sprint, the unexpected upset. For a moment, we're all just fans, cheering for excellence wherever it comes from.

Until next time,

Deena