Targeting cash transfers in a crisis

Using machine learning to identify people in need

This Giving Season, I’m taking part in a campaign alongside other Substack writers to support GiveDirectly, which focuses on sending direct cash transfers to people facing extreme poverty and crisis. This post reflects my views, and is separate from my employment at Coefficient Giving. I’ll be matching the first $500 in donations to GiveDirectly through this link.

Cash transfers are built on a basic premise: instead of deciding in advance what people in need should receive, you give them cash and let them decide how to use it. Part of its advantage is simplicity. But even though cash is more straightforward than deciding whether to distribute food, fertilizer, school supplies, or vouchers, it doesn’t eliminate a core problem: figuring out who should receive it, and getting it to them in time.

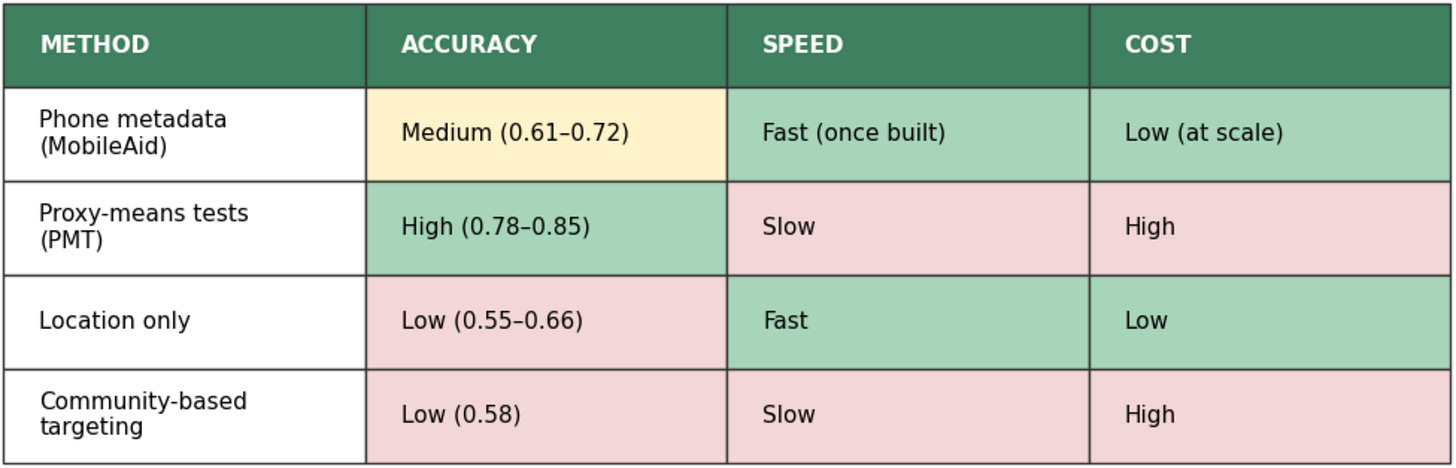

In normal circumstances, governments and aid groups rely on tools like proxy-means tests, social registries, or community nomination to identify low-income households. Household surveys are accurate, but slow and expensive to run. Social registries are cheaper, but often out of date. This trade-off between speed and accuracy is one of the perennial problems in grant-making — you can get money out the door much faster if you are willing to sacrifice a bit of certainty. GiveDirectly is dealing with this using a new, AI-based method that’s quite interesting.

Imagine an increasingly common scenario: a flood hits, or a hurricane makes landfall, or a pandemic shuts down local economies. You want to get cash to the people who need it most — and quickly, before savings run out, food prices spike, or families start selling assets. But in many of the places most exposed to these shocks, there’s no reliable, up-to-date list of who is most in need.

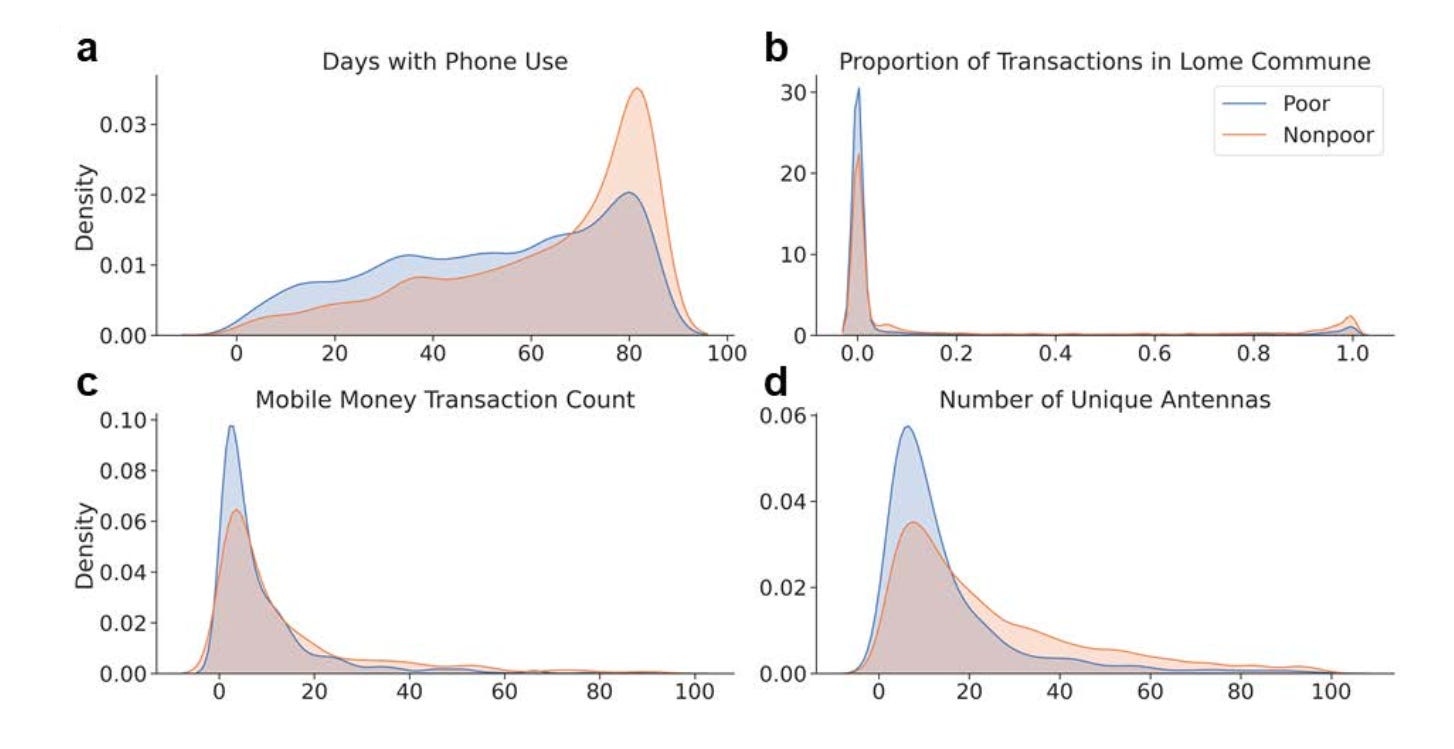

To get around this bottleneck, GiveDirectly has started experimenting with a different approach in some crisis settings: using anonymized mobile phone data and machine learning to identify people likely to be in need. The idea is not that phones “measure poverty” directly, but that patterns of phone use correlate with economic status. Intuitively, call frequency and duration, SMS use, mobile money and airtime recharges, the diversity of contacts, and how much a phone moves between cell towers are all related to income and vulnerability. People with fewer social connections, less frequent recharges, and more restricted movement are, on average, more likely to be poor.

They call this approach MobileAid. The validation is relatively straightforward: train machine-learning models on anonymized phone data and then validate them against the in-person household surveys that are considered gold standard. That allows for benchmarking against what we know works. In practice, phone data is used to generate a shortlist of households likely to be in need, after which people can self-enroll via text message or a call center, be remotely verified, and receive mobile money payments. This means cash can reach those who need it sometimes within days or even hours.

So how well does this actually work, relative to the tools governments already use?

The first real-world test came in Togo during COVID-19, when lockdowns made door-to-door surveys infeasible. Working with the Togolese government, researchers used phone metadata and machine learning to help identify people eligible for emergency cash transfers when lockdowns made in-person surveys impractical.

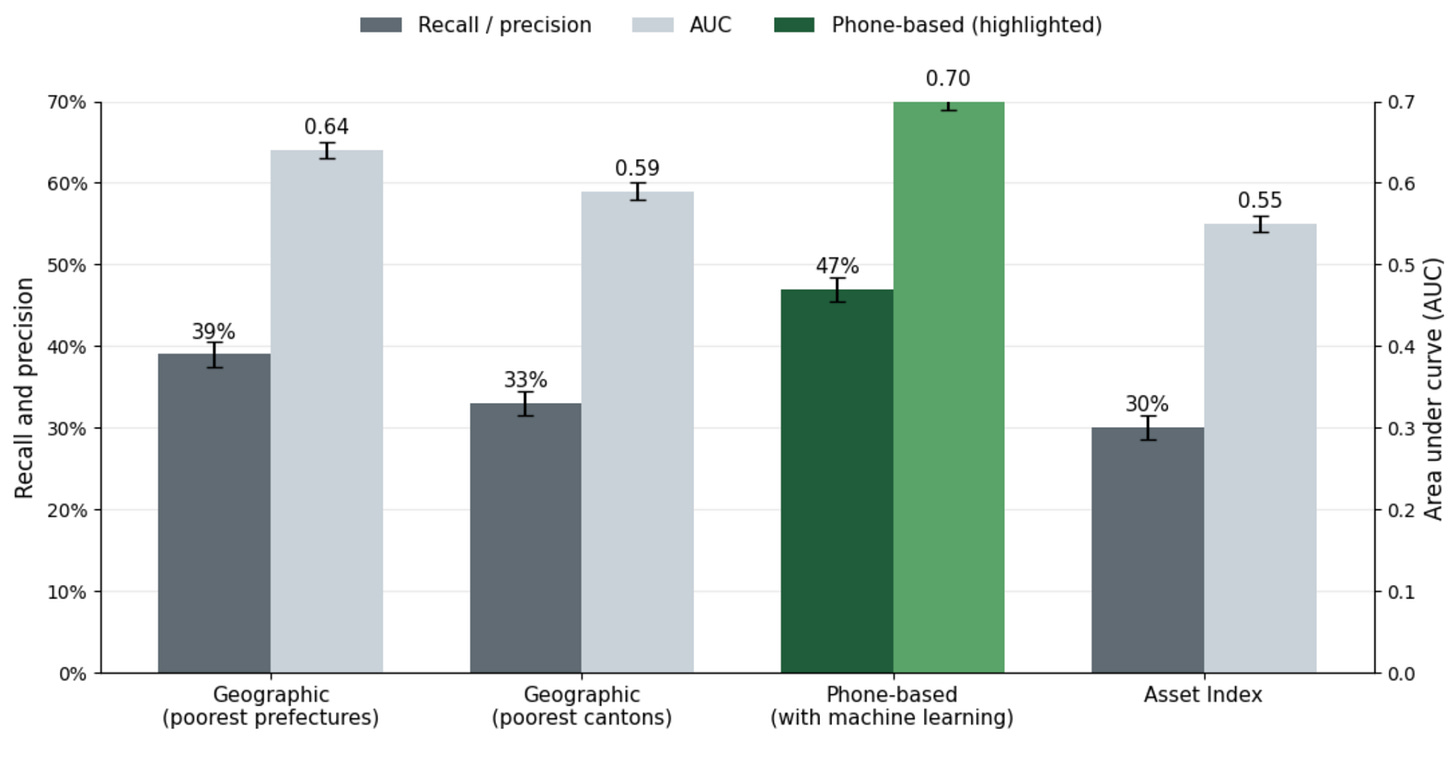

The program reached over 138,000 people, and when researchers later compared different targeting approaches, the machine-learning method reduced exclusion errors by 8-14% relative to geographic targeting. Extrapolating a bit from the sample, this means roughly 4,000-8,000 additional people who should have received aid actually did.

The authors emphasized that phone-based targeting worked best as a rapid, supplemental tool in crisis settings, rather than a wholesale replacement for traditional surveys — this seems right, and appropriately cautious, given the accuracy-coverage tradeoffs.

GiveDirectly has since launched studies testing MobileAid in Bangladesh, Malawi, Kenya, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. In Bangladesh, for example, phone metadata was consistently more accurate than community targeting, and though it was less accurate than full proxy-means tests, it was far faster and cheaper to deploy at scale. When researchers simulated large programs operating under tight budgets — screening many households with limited funds — phone-based targeting showed the greatest welfare impact per dollar spent, exactly because it could move quickly when surveys could not.

Overall, it seems that phone-based ML-assisted approaches aren’t the most precise ones available, but they outperform most rapid alternatives and dramatically reduce the cost and time required to act. For emergency scenarios, in which who is in need changes quickly and getting help sooner can be dramatically better, it’s easy to see why this is an attractive tool.

One obvious concern with algorithmic targeting is bias: do these models systematically exclude already-vulnerable groups? In the Togo study, researchers explicitly compared error rates across gender, age, religion, household type, and ethnicity, and found no evidence that the machine-learning approach was more likely than other targeting methods to wrongly exclude any demographic groups. I was initially skeptical that these models wouldn’t have demographic bias given differential phone ownership and use, so this was a notable and important aspect of the study for me.

That said, the biggest risk seems to be not model bias so much as coverage. Phone-based targeting can only reach people who have access to a phone. While mobile penetration is now very high in many low- and middle-income countries, around 97% of households in Bangladesh and over 90% in Kenya have at least one phone, ownership is still lowest among the very poorest households. This increases the risk of excluding precisely those most in need.

MobileAid systems are also typically more expensive to set up than traditional in-person surveys. They require regulatory approval, telecom partnerships, and technical integration. But once those systems are in place, they become much cheaper in terms of marginal cost — that is, per additional household screened. In Bangladesh, researchers estimated that while in-person proxy-means testing remained the most accurate method, phone-based targeting was the most cost-effective option for large programs operating under tight budgets, where governments might spend only $10-50 to screen each household and need to reach many people quickly.

GiveDirectly’s response to these tradeoffs strikes me as pragmatic: hybrid designs that use phone data where it’s strong but maintain in-person outreach to avoid excluding the poorest households. In Malawi, for example, about 35% of recipients were identified using phone metadata, with the remaining 65% enrolled through in-person outreach. The combined approach cut the cost of identifying and enrolling each additional recipient roughly in half compared to a fully field-based program, while still reaching households without phone access. Similar hybrid models are now being tested in Kenya, where households in flood- and drought-prone areas are enrolled both digitally and in person so cash can be sent quickly when early-warning systems predict extreme weather.

During humanitarian crises, phone-based targeting offers a way to reach vulnerable households more quickly and more cheaply than existing rapid-response methods. In the wake of an unfolding crisis, any delays in aid can significantly impact the course of events: they change behavior, force bad tradeoffs, and lock in losses that can’t be undone later. Selling livestock, skipping meals, pulling children out of school are not as easy to solve with help after the fact.

Fascinating look at adaptive targeting methods. The coverage-accuracy tradeoff is really well articulated here, especially the point about phone ownership being lowest among the poorest households, which creates a catch-22. The hybrid approach in Malawi (35% phone data, 65% in-person) seems like the pragmatic middle ground. What caught my attention is the speed advantage mattering most when crises unfold rapidly, I remeber reading about delays in hurricane relief where traditional surveys took weeks while people were making irreversible decisions about selling assets. The ML bias testing across demographic groups is also realy important transparency.