How much do you value a year of life?

Part 1: What people say

In Denmark, people say a year is worth about $24,000. In Japan, maybe $67,000. Not infinite. Not priceless. Just... a number.

It sounds cold to put a price on life, but we do it every day. When an insurance company decides whether to approve a drug, when a hospital allocates ICU beds, or when a development agency funds one intervention over another, they are implicitly answering the same question: how much are extra years of life worth?

This post is part 1 in a series on how people and policymakers actually value those trade-offs. Here, I look at what people say when asked directly how much a healthy year of life is worth to them. The answers are oddly consistent—and consistently strange. In part 2, I’ll explore what people actually do: the risks they take, the jobs they accept, and the trade-offs they make with real money and real danger.

If you ask people directly how much a year of life is worth, they will usually try to answer. They’ll pause, reflect, and perhaps wince — but they’ll tell you. Economists call this the stated preference approach, and for decades they’ve used it to tease out the monetary value people assign to health and longevity. The idea is simple: present people with hypothetical scenarios involving risks to life or health, and ask what they'd be willing to pay to reduce those risks. Aggregate the answers, and you get a kind of market price for life, at least in theory.

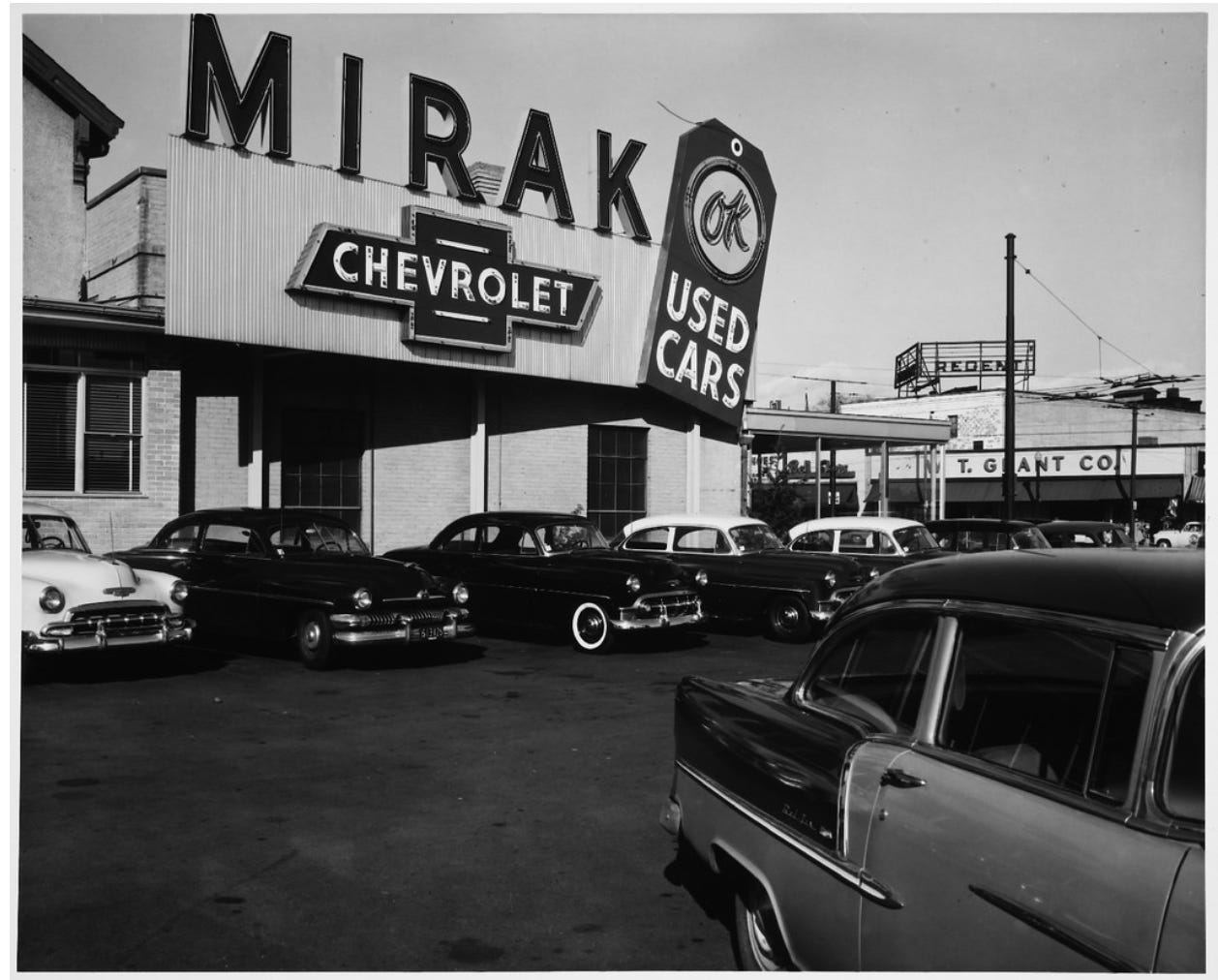

In Denmark, one economist asked a cross-section of the population how much they’d personally pay, out of pocket, for a treatment that would give them one extra quality-adjusted life year (QALY) – defined as a year of perfect health. The average answer was about DKK 88,000. This was $14,660 in 2003 – or ~$24,000 in today’s dollars. That’s not particularly high for what is an almost stereotypically wealthy and health-conscious country. In the Netherlands, a similar study found that people would pay a bit more: between €12,900 and €24,500. Converted into today’s dollars, that’s $24,000-45,000. Instead of inferring preferences from choices between health states, the Dutch researchers just asked people to name their price. What’s one year of full health worth to you? Turns out that for many people, it’s somewhere between a used car and a new one.

But when you add some risk, something strange happens. In a follow-up study, the Dutch team asked people how much they’d pay for a treatment that had a chance, say 10%, 40%, 70%, or 90%, of working. Just like in real life, where everything from malaria nets to surgeries to vaccines reduce your risk of illness but don’t guarantee safety. Under standard economic theory, your willingness to pay should scale with the probability: if you'd pay €90,000 for a 90% chance of a drug working, you’d pay about €9,000 for a 10% chance of the same drug working. But that’s not what they found.

Instead, people’s willingness to pay dropped far less than expected as the probability declined. For example, someone might pay €60,000 for a 90% chance, and still offer €25,000 for just a 10% chance — nearly three times more than expected. If you extrapolate under the assumption that people’s willingness to pay should scale linearly with probability, their answers implied a QALY valuation of over €250,000 ($400,000 today); over three times what the previous study suggested. This was the same researchers, same methodology, and same country.

To figure out how much people were overweighting, they treated responses to the 90% chance as a reasonable anchor, assuming people process near-certainty more rationally, and compared it to how they behaved at lower probabilities. Based on those comparisons, they estimated that people were treating a 10% chance more like 30-40%, inflating the likelihood. Once they corrected for that distortion, the implied value people placed on a QALY fell from €250,000 down to a consistent range of €80,000 to €110,000 ($130,000 to $190,000 in today’s terms).

It’s been shown across many settings that people overweight small probabilities, which could cause them to overestimate the benefit of the treatments. Maybe when the question got more complicated, the answer also felt harder to pin down – and respondents defaulted to playing it safer with their health.

In Japan, researchers explored a different angle: what if the health you’re buying is relief from something truly awful? Participants were asked how much they'd pay for a treatment for a specified illness. Across scenarios, the health gain was fixed — either 0.2 or 0.4 QALYs — but the initial health states ranged from mild to severe, based on EQ-5D utility scores. The results showed that people were willing to pay more per QALY when the starting condition was worse. For mild states, the average valuation was around JPY 2 million ($25,000 today) per QALY; for severe ones, closer to JPY 8 million ($100,000). The overall average was JPY 5 million ($67,000), aligning with other Japanese estimates.

This finding challenges a central assumption of cost-effectiveness analysis: that a QALY is a QALY, regardless of context. In theory, a one-QALY gain should be valued the same whether it’s achieved by relieving mild pain and extending someone’s life or by rescuing someone from severe illness. But, in practice, people placed a higher monetary value on QALYs gained from more severe states. That suggests health improvements aren't perceived as interchangeable units — people care not just about how much health is gained, but from what baseline state. For policymakers, this raises tough questions: should interventions that relieve extreme suffering be funded at a higher cost per QALY? Should thresholds for cost-effectiveness vary based on severity? Studies like this suggest many people would say yes.

Across the ocean, a team in the U.S. posed a similar question, but grounded it in a familiar pain: shingles. They asked people, some who’d had shingles and some who hadn’t, what they’d pay to avoid contracting the disease and suffering a bout of temporary pain and disability. The results spanned the map. Median values clustered around $7,000 to $11,000 per QALY ($10,000-$15,000 today), but the means were much higher, around $26,000 to $45,000 ($36,000-$63,000), thanks to a few people who were willing to pay eye-watering amounts. Those who’d actually experienced shingles – well, unsurprisingly, they were willing to pay more. In this case and the Japan study, people seem to be willing to spend more to avoid pain they remember or can clearly imagine, as in the case of specific, painful diseases.

And in Spain, a group of researchers added another twist: what if you’re paying with your own money versus paying through taxes? When asked what they’d pay out of pocket for a year of perfect health, people gave an average answer of €10,119 ($17,000 today). But when the question was reframed as a public cost, in terms of what society should pay through taxes, that number nearly tripled to €28,187 ($48,000 today). People think it’s worth spending more collective money than their own. Maybe this is because public spending feels more abstract – a rise in taxes can seem less concrete than spending out of pocket, even if by the same amount – or because we see health as a natural shared social responsibility, or because it feels indulgent to spend for another year of perfect health for oneself.

Taken together, these studies form a patchwork portrait of how people say they value life. The numbers vary, but not wildly: when converted into today’s U.S. dollars, most estimates fall between $25,000 and $100,000 per healthy life-year, somewhere between the cost of a Rolex and a year of college. A 2022 systematic review of 39 studies and 511 observations globally found a mean value of $52,619 per QALY ($67,000 today), with some higher estimates in specific regions (for example, about $98,450 in Quebec). That’s a provocative finding. It suggests that, at least in the abstract, people treat an extra year of life less like a priceless treasure and more like a durable good: valuable, yes, but bounded.

These numbers aren’t uniform, and one of the clearest patterns is that, unsurprisingly, wealth matters. People in higher-income countries tend to give higher valuations, and, within countries, richer respondents are willing to pay more. In the Netherlands study mentioned before, for example, willingness to pay per QALY varied from €5000 in the lowest to €75,400 in the highest income group — ~$10,000-140,000 in today’s dollars. Education sometimes raises valuations too, though inconsistently, while older respondents tend to report lower willingness to pay than younger ones.

People are also more generous when costs are distributed across society as a public good than when they’re asked to pay out of pocket. When the stakes feel more emotionally charged, like a disease you’ve personally experienced, the numbers tend to climb. In health valuation, as in so many other domains, we do not coldly optimize. We react to stories, to fairness, to mental images of who might suffer and how. The same life, the same year of health, can be deemed two or three times more valuable depending on whether the question feels personal or collective, distant or near.

In spite of the many survey studies that have been conducted, there are still important open questions about this work. Why exactly are people more generous when the money comes from taxes rather than their own wallets? What are they imagining when asked to value a “year of full health”? These factors reveal how much context, framing, and personal experience shape people’s responses.

That matters for policymakers. If valuations shift considerably depending on how a question is asked or how vivid the scenario feels, it could mean we are undervaluing diseases that are abstract, unfamiliar, or hard to picture, or underestimating willingness to support public health spending by relying on estimates based on private trade-offs. These gaps deserve more scrutiny, especially if we're using these numbers to decide when to spend on health.

But whatever their quirks, these survey results give us something concrete: a set of numbers that anchor abstract talk of health and safety to the world of money and trade-offs. They are imperfect, but they are honest in their own way. They tell us that when asked to put a price on life, people don’t reach for the infinite; they reach for a figure they can imagine paying, or taxing, or justifying.

I intend for this to be part 1 in a series of posts about valuing trade-offs between health and income. In the next one, I’ll look at what happens when people don’t just answer surveys, but instead make real trade-offs between money and risk. If you’re interested in the ways we reveal our values through action, stay tuned. And if there’s a specific question you’re interested in related to how we value health, let me know.

Dear Deena, can we translate part of this article into Spanish with links to you and a description of your newsletter?

Such an interesting and well constructed piece, thanks Deena.

"...at least in the abstract...people treat an extra year of life less like a priceless treasure and more like a durable good: valuable, yes, but bounded." i would hypothesise that it's the case that rather than treating life like a durable good, respondents are implying that the treatment itself is the durable good (within the context of the various surveys you reference). Baked into the responses are the real world costs and the perceived probabilities those costs imply. Are Danes sceptical of more expensive treatments because they have good faith in the ones that are available to them at a lower price? (sorry to ramble)